Resilience and Recovery in the Northeast Valley

In 2022, the California Community Foundation (CCF) launched the Regional Recovery Hub to strengthen place-based coordination in Los Angeles County regions that were most heavily impacted by COVID-19. CCF contracted with six regional leads to build recovery action plans and distribute financial resources in their regions. Regional leads convened a table of local organizations to guide and implement the work in each region.

NDSC provided data and technical assistance support to each of the regions and their network of local community partners. This data story is part of a series on CCF’s Regional Recovery Hub and provides insights into the work being led by Pacoima Beautiful in the Northeast San Fernando Valley. To explore additional data for this region, view it on the NDSC map here.

Community-Centered Collective Action

Pacoima Beautiful was founded in 1996 by five mothers who – disturbed by the sight of trash and toxic smells they encountered while walking their children to school – organized some of Pacoima’s first community clean-ups and tree planting events. Through community-centered collective action, they built Pacoima Beautiful, the first and only environmental justice organization serving the Northeast San Fernando Valley.

This ethos of resiliency and activism is central to the Northeast Valley, a multicultural, multigenerational working-class community. The region comprises eleven neighborhoods (shown in the map below) and is home to just over 580,000 residents, 44% of whom are immigrants. Just under 70% of residents identify as Hispanic or Latino/a, among whom Mexican, Salvadorian and Guatemalan heritages are well represented. Hover over a neighborhood on the map below to see demographic information about that area.

Median earnings for residents in the Northeast Valley have failed to keep pace with other places throughout the county in recent years. (Earnings are defined as the wage or salary income that an individual receives from their employment, including self-employment). As shown on the graph below, in 2020, median earnings in the Northeast Valley were approximately in line with the LA County median of $35,100. Even after correcting for inflation, between 2020 and 2022, countywide median earnings grew by nearly $6,000 to $41,100. By comparison, median wages in the Northeast Valley grew by less than $1000 over the same time period. This trend underscores a larger story of how deeply the community in the Northeast Valley was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

An Epicenter for COVID-19

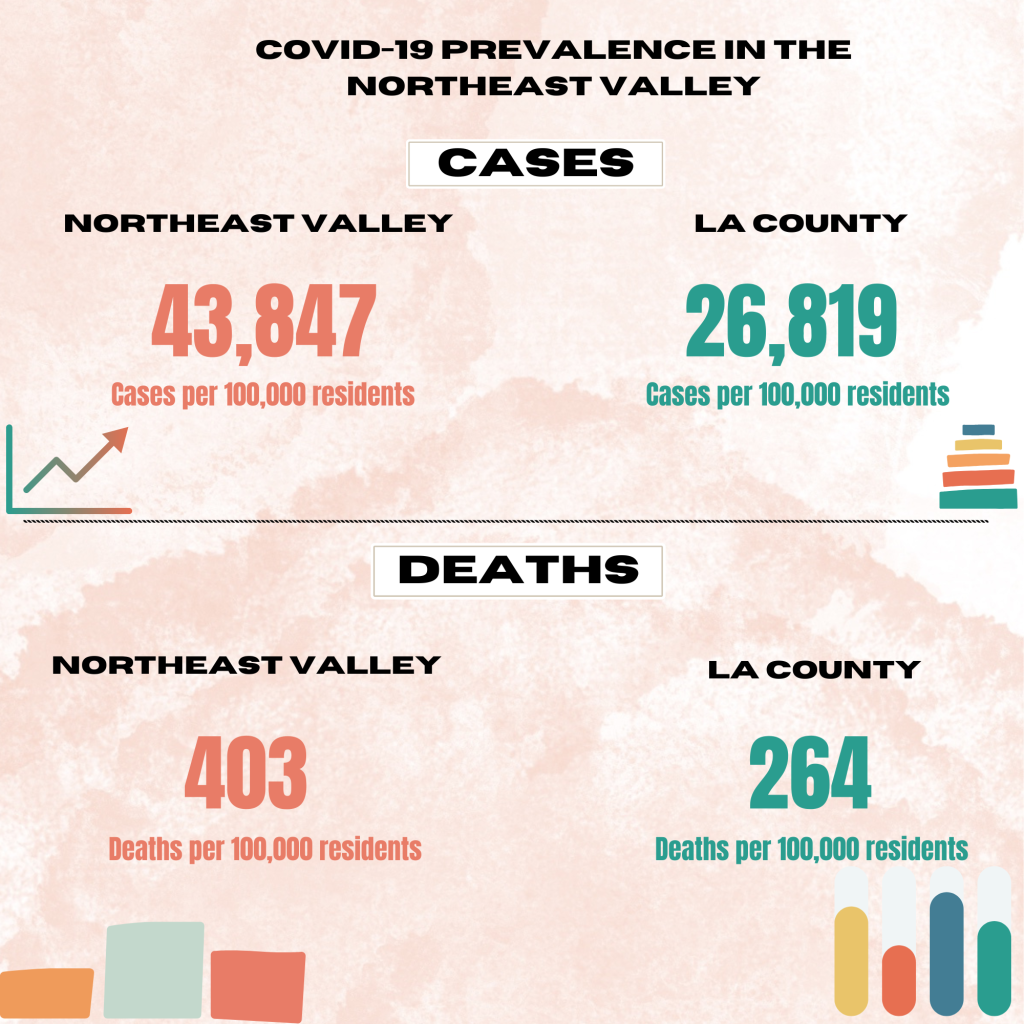

In December 2020, the LA Times published an article noting that 19 of the 25 LA County communities with the highest COVID-19 infection rates were located in the Northeast San Fernando Valley. According to the LA County Department of Public Health, between April 2020 and October 2023, the Northeast Valley experienced a rate of about 43,800 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents compared to around 26,800 cases per 100,000 residents countywide. Similarly, the Northeast Valley also experienced significantly higher COVID-19 death rates than the county average, shown in the infographic below. Several structural and environmental factors likely led to COVID’s disproportionate impact in this community.

As of 2022, 18% of Northeast Valley households were considered “overcrowded,” defined as more than one person per room of a given housing unit, compared to 11% of households countywide. Research has shown that overcrowded households in LA County had higher rates of COVID-19 deaths than other households during the peak of the pandemic, likely due to the lack of available spaces to isolate from sick family members. In addition to fewer indoor spaces, Northeast Valley residents have also been exposed to greater outdoor environmental risks than many other LA County residents. Expand the boxes below to explore the various types of environmental risks that impact communities in the Northeast Valley (CalEnviroScreen 4.0).

Definition

Living in proximity to landfills, transfer stations, composting facilities, and other sites designed to store and process waste.

Health Risks

Waste gases such as methane and carbon dioxide reduce air quality, and waste sites can seep toxic chemicals into the water supply, leading to an increase in likelihood for birth defects.

Focus Neighborhood

Sun Valley experiences more exposure to pollutants from solid waste facilities than 85% of the other Los Angeles County neighborhoods.

Definition

Fine particulate matter, or PM2.5, are tiny particles less than 2.5 micrometers wide that float through the air. Because they are small enough to penetrate the lungs, measuring PM2.5 is an often-used indicator for air quality.

Health Risks

Fine particulate matter can enter the lungs and even the bloodstream, causing adverse health effects such as lung and heart disease.

Focus Neighborhood

Lake Balboa experiences more exposure to PM2.5 particles than 99% of other Los Angeles County neighborhoods.

Definition

Living in proximity to permitted hazardous waste facilities and hazardous waste generators.

Health Risks

Living near hazardous waste sites is associated with higher rates of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Focus Neighborhood

San Fernando experiences more exposure to pollutants from hazardous waste facilities than 90% of the other Los Angeles County neighborhoods.

Definition

Living near areas of high traffic volume and longer roads leads to higher exposure to vehicle emissions.

Health Risks

Traffic exhaust contains toxic chemicals that pollute the air and contribute to heart and lung disease, cancer, and lower life expectancies.

Focus Neighborhood

Mission Hills has worse exposure to pollutants from traffic than 92% of the other Los Angeles County neighborhoods, likely due to intersections of SR 118, I-5, and I-405.

Definition

The share of residents that live within a half mile of a public park that was evaluated to be of “good condition” by the 2022 LA County Parks Needs Assessment.

Health Risks

Parks and open spaces can benefit one’s health, foster a strong community, increase children’s physical activity, reduce stress, and improve academic performance.

Focus Neighborhood

54% of Pacoima residents do not live within a half mile of a public park considered to be in good condition.

As a result of these intersecting environmental risks, Northeast Valley residents may have had fewer opportunities to convene safely outdoors during the height of the pandemic. For example, in Pacoima, a community with limited access to good quality parks, 30% of residents reported that they didn’t participate in regular physical activity outside of work in 2020 (CDC BRFSS 2020). In addition to lack of outdoor spaces, exposure to environmental pollutants also increases risk for a variety of health conditions that can make COVID-19 infections more severe. Northeast Valley residents report higher rates of many such conditions including diabetes, asthma, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and coronary heart disease, while also having access to fewer hospital beds per capita than the LA County average.

Economic Impacts of the Pandemic

In addition to environmental and health factors in the community, many Northeast Valley residents may have had increased risk for exposure to COVID-19 at work. As of 2022, “Healthcare and Social Assistance” was the sector employing the largest share of Northeast Valley residents. The essential nature of healthcare and social assistance jobs placed workers at greater risk of contracting the virus and created a mental health crisis among workers in those industries.

The pandemic also impacted workers in other key industries employing many Northeast Valley residents such as manufacturing, construction, and retail trade. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, hours worked in the manufacturing sector across the U.S. fell by almost 40% after the start of the pandemic, the largest decline since World War II. According to the Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, there were roughly 6,000 fewer jobs across all industries in the Northeast Valley in 2020 compared to 2019.

In addition to individual workers, businesses and community-based organizations (CBOs) also faced economic challenges. Some larger and well-established organizations were able to take advantage of pandemic-related economic relief and loan opportunities, but many “microentrepreneurs” (or those with very new and/or small-scale business ventures with limited resources, many of whom are not yet fully registered businesses) were unable to utilize these supports.

Pacoima Beautiful interviewed several microentrepreneurs and leaders of community-based organizations who participated in Regional Recovery Hub efforts about their economic challenges during the pandemic. Participants reported high stress levels due to tight budgets and limited support networks. The pandemic reduced discretionary spending and increased cautionary measures for households, meaning most business – particularly in-person sales and services – slowed to a halt. Even when participants attempted to apply for small business relief funds, they often faced confusing application processes or numerous denials. This financial uncertainty, increased workload, and isolation commonly led to feelings of burnout and mental health challenges among interviewees. Amidst stress and burnout, however, participants still found creative ways to expand their business sales, including tapping into online communities like Instagram.

The Recovery Hub Socially Organized Leaders (SOL) Training Institute

Given the pandemic’s widespread impact on the Northeast Valley, Pacoima Beautiful has recently expanded on their environmental justice work to focus on helping local microentrepreneurs and community-based organizations recover from COVID-19. In partnership with the California Community Foundation, Pacoima Beautiful launched the Recovery Hub Socially Organized Leaders Training Institute (SOL-TI) in 2023. SOL-TI is a capacity-building program for microentrepreneurs and community-based organizations in the Northeast Valley. With a series of training workshops and a $4,000 grant awarded at the end of the program, SOL-TI ensures that those who may not typically have access to such resources are provided with the support they need to thrive. These individuals often do not qualify for certain grants or alternate funding sources, making programs like SOL-TI invaluable to their success.

"Our participation in the Recovery Hub SOL-TI Grant funding has greatly benefited our nature-based parent support groups. This funding has allowed us to purchase materials used in our community garden, making participation more accessible and comfortable. Items include shade, storage, native plants, guest facilitators, and more. These funds have also allowed us to improve our childcare by purchasing toys and games for the children."

- Champions in Service

Training workshops have included a range of key topics to help leaders of small businesses and organizations grow their operations, including branding and communication, grant writing and fundraising, the importance of data, and professional development coaching. Other workshops focused on broader topics like defining systems-level change, helping participants understand how their efforts can work together to improve wellbeing outcomes across their community. Recognizing the deep mental health toll both of the pandemic as well as decades of economic and environmental disinvestment on Northeast Valley residents, SOL-TI also included workshops focused on healing racial trauma through arts and culture practices. By participating in SOL-TI, microentrepreneurs and community leaders not only receive guidance from experts, but also have the opportunity to learn from each other’s experiences, fostering a sense of community and collective growth.

“Recovery Hub SOL-TI funding has had a great impact on our organization. We are now able to rent space at the Life Center at Mission City church two days a week to offer free yoga and mindful classes to the community. We were also able to plan our annual Fall Mental wellness festival.”

- The Playroom’ Alternative Therapy Center for Children

During its first iteration, SOL-TI served four cohorts of 51 participants. Although Pacoima Beautiful has just begun this programming around economic recovery and small business support, their decades-long values of community-centered collective action are at the center of the work. Leveraging their longstanding ethos of resident-led movements, Pacoima Beautiful’s SOL-TI is building a regional network of organizational leaders and entrepreneurs dedicated to building a thriving Northeast San Fernando Valley.

Pacoima Beautiful Community Partners

Casa de Cultura Maya, Mend, Boys and Girls Club, Strength Based Community Change, Mexicanos 2070, Tia Chuchas, Chica’s Mom, Mujeres de Hoy, Somos Familia Valle, Pueblo y Salud, El Nido Family Centers, Womyns Healing Resource Clinic, Champions in Service, Integrative Communities dba The Social Impact Center, Behind the Beet, Classroom of Compassion, AWOKE, The Playroom Alternative Therapy Center for Children, Khalsa Food Pantry / Khalsa Care Foundation, Grid Alternatives

Raíces del Valle, Asociacion de Paraguayos en la Costa Oeste (APCO), San Fernando Valley Refugee Children Center, Hazzards Barbershop, Futcorner, Vision Elevated, La Casa Del Doctor, YHK Unlimited, Vero’s Catering, Valley Views, Miracle House Cleaning, Show Me your Faith, White Ice Cream, Rustica, FGLSM Electric SO-CO, Sun Valley Wholesale Ice Cream, Ovis Fragancias, Manos Morenas Como Lo Quieres Catering, Dulce Beauty Salon, YESMIA Flowers, Carwash Charly, Turimports, Emmanita Toy Store, David- Barber, Mortgage Loan Origination, Tiffany’s Fashion, Berries Grove, Karen & Sons M.O.N.O. Treats, Cultures and Communities LLC, Chrysalis (Change Lives), ConnectoPod Learning Center, Filipino Migrant Center, Helping Hands Resource Center, Iglesia Bautista El Buen Pastor, Main Street Canoga Park, Insight Center for Community Economic Developement, Keep Youth Doing Something (KYDS), Lifeline Rehabilitation and Prevention Center, Kidneys Quest Foundation, Plaza Comunitaria Sinaloa, Qweerty Gamers, SCGA Junior Golf Foundation, SFV Japanese American Community Center (JACC), Shift Our Ways Collective, The Valley of Change, The Writing Schools LA, Why We Give

Authors & Contributors

Elly Schoen

Elly Schoen (she/they) is the Systems & Data Manager at Neighborhood Data for Social Change, a project of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate. Prior to joining the Lusk Center, Elly worked at the USC Price Center for Social Innovation for six years. Her various roles included building out the Center’s data infrastructure, launching the Homelessness Policy Research Institute (HPRI) and the Neighborhood Data for Social Change (NDSC) platform, and training graduate research assistants in foundational data and research skills. In their current role, Elly continues to manage the NDSC platform, where they work with community-based partners to use data to inform equitable policies and build power in Los Angeles County neighborhoods.

Dan Hoornbeek

Daniel Hoornbeek is a current Master of Public Administration (MPA) student in USC’s Price School of Public Policy. Dan holds a B.S. in Economics and Spanish with a minor in Music from Ohio State University. His primary interests include nonprofit management, particularly in the realm of arts, service, and advocacy nonprofit organizations, as well as education policy and social policy. Dan has prior experience in the state legislature, state agencies, and nonprofit organizations and also currently works as a Research Associate with the USC Center for Economic Development. Additionally, he serves as a Communications Chair with the student organization Mentorship for an Accessible Price (MAP). Dan hopes to continue applying his experience to influence positive change for historically marginalized communities in Los Angeles and beyond.

Other Contributors: Cameron Yap, Emily Phillips, Caroline Ghanbary

Sources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2004). Prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity–35 States and the District of Columbia, 1988-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004 Feb 6;53(4):82-6. Link.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, October 24). Transcript: Health Workers Face a Mental Health Crisis. CDC. Link.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 12). Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19: Information for Healthcare Professionals. CDC. Link.

LA County Daily COVID-19 Data. (n.d.). LA County Public Health. Link.

Sugg, M. M., Runkle, J. D., Ryan, S. C., Singh, D., Green, S., & Thompson, M. (2023). Crisis response and suicidal behaviors of essential workers and children of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974). Link.

U.S. manufacturing output, hours worked, and productivity recover from COVID-19 : The Economics Daily: U.S. (2022, October 7). U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Link.

Varshney, K., Glodjo, T., & Adalbert, J. (2022). Overcrowded housing increases risk for COVID-19 mortality: an ecological study. BMC Res Notes, 15(126). https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs13104-022-06015-1. Link.

Vives, R. (2020, December 1). San Fernando Valley’s Latino neighborhoods staggered by L.A. County Virus outbreak. Los Angeles Times. Link.