The SGV Collaborative: Collective Action for Environmental Justice

In 2022, the California Community Foundation (CCF) launched the Regional Recovery Hub to strengthen place-based coordination in Los Angeles County regions that were most heavily impacted by COVID-19. CCF contracted with six regional leads to build recovery action plans and distribute financial resources in their regions. Regional leads convened a table of local organizations to guide and implement the work in each region.

NDSC provided data and technical assistance support to each of the regions and their network of local community partners. This data story is part of a series on CCF’s Regional Recovery Hub and provides insights into the work being led by Active SGV in the San Gabriel Valley. To explore additional data for this region, view it on the NDSC map here.

An Integral Connector

The San Gabriel Valley is home to nearly 2 million residents across 400 square miles. The area is the largest majority Latino and Asian American region in the United States. The San Gabriel Valley is an integral part of the local, national, and international goods movement economy, containing highways and railways that connect the nation’s two busiest ports to many other regions throughout Southern California and the United States. The Alameda East Trade Corridor, a stretch of over 70 miles of railroad through the San Gabriel Valley, is among the nation’s busiest rail corridors, carrying 16% of all port-destined containers in the United States. Residents of the region are also connected by a shared water basin spanning 167 miles.

The neighborhoods in the region are not a monolith. For example, according to 2022 American Community Survey (ACS) data, San Marino, the highest-income neighborhood in the region, has a median household income of $185,400, nearly three times higher than that of El Monte, the lowest-income neighborhood in the region. Further, despite being home to nearly one-fifth of Los Angeles County’s population and an integral part of the regional economy, the area is often left out of funding conversations and according to local leaders, has fewer community-based and nonprofit organizations than other regions in the county.

“The SGV is home to some of the most pollution-burdened communities in California, an environmental injustice that requires collective action and regional collaboration.”

SGV Collaborative

Through the SGV Collaborative, Active SGV facilitated network building with other regional organizations to build a regional vision for a more just and sustainable future. Through a collaborative process, the initiative focused on a subset of the region that the table identified as the areas with the highest need. As of 2022 ACS estimates, this geography is home to approximately 1.2 million San Gabriel Valley residents and is shown on the map below.

As shown on the graph below, fifty-four percent of residents identify as either Hispanic or Latino/a and an additional twenty-eight percent identify as Asian (2022 ACS 5-year estimates). Hover over various boxes within the Latino/a and Asian bars to see a further breakdown of these racial/ethnic groups. All groups who make up over one percent of the total population are shown.

Learn more about the specific groups that make up the “Other” labels in the section below.

The “Other Race” group includes individuals that selected American Indian/Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, Other Race, or Two or More Races on the census.

The “Other Latino/a Countries of Origin” section of the Latino/a bar includes individuals that selected Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Costa Rican, Guatemalan, Honduran, Nicaraguan, Panamanian, Salvadorian, Argentinean, Bolivian, Chilean, Colombia, Ecuadorian, Paraguayan, Peruvian, Uruguayan, Venezuelan, or Other Latino/a Country on the census.

The “Other Asian Countries of Origin” section of the Asian bar includes individuals that selected Indian, Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Burmese, Cambodian, Chinese, Filipino, Hmong, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Lao, Malay, Mongolian, Nepalese, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Taiwanese, Thai, Vietnamese, or Other Asian Country on the census.

Further, just under 40% of residents in the SGV Collaborative area are immigrants. As of 2022, 16% of households in the area were considered “linguistically isolated,” meaning no one over the age of 14 reported speaking only English at home or speaking English “very well” as a second language (2022 ACS 5-year estimates). English proficiency can play an important role in accessing certain types of jobs and other social service and healthcare resources, and is correlated with higher academic performance in K-12 students. Across some pockets of the region, shown on the map above, as many as half of households are linguistically isolated (2022 ACS 5-year estimates).

This data story discusses key environmental, health, transportation, social connectedness and housing issues faced by the subset of the region that the SGV Collaborative is focused on, as well as their work to collaboratively engage residents and fuel investment to the San Gabriel Valley.

The Cost of Connection

Serving as a key part of the international goods movement economy comes with a cost to residents of the San Gabriel Valley – the region is home to some of the most pollution-burdened communities in the county and the state. Pollution burden, a measure by CalEnviroScreen, estimates potential pollution exposures in a community from traffic density, pesticide use, toxins from facilities, drinking water and air contamination, and more. According to this measure, over 200,000 residents in the SGV live in an area ranked in the 90th percentile or higher for pollution burden compared to other places in Los Angeles County.

Tackling environmental justice in the SGV is complex due to the range of sources of pollution throughout the region. For example, areas with particularly high exposure to particulate emissions from vehicle exhaust tend to be those that are located in close proximity to one of the many freeways running throughout the region. Flip through the boxes above the map (below) to learn more about the different types of pollution affecting communities throughout the San Gabriel Valley.

Mobility and Access in the San Gabriel Valley

While the five major freeways that run through the San Gabriel Valley contribute to pollution in the region, they also inform transportation options available to residents. Only 3% of residents use public transportation to commute to/from work the majority of the week, while 72% of residents drive to work alone (2022 ACS 5-year estimates).

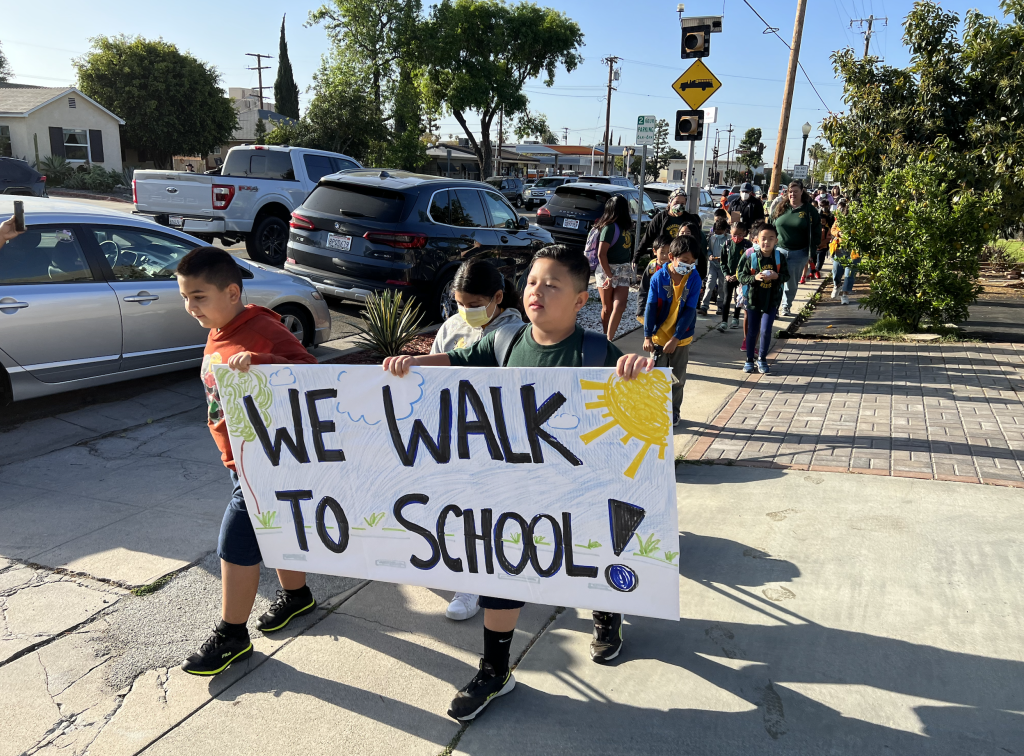

Mobility accessibility contributes to the high percentage of car-users in the region. Insufficient direct transit routes deter residents from opting for public transportation over driving. Despite this issue, transportation funding tends to be allocated to other L.A. County areas. The construction of the Pomona to Montclair extension project for the Gold Line lost out on 2023 funding as state transportation officials chose instead to give more than $400 million to the Inglewood Transit Corridor project. Biking options have also been underfunded – Eaton Wash Greenway, a bike/pedestrian path that would carry people from Pasadena to El Monte, has not been getting enough funding by the County, leading to delays. Viable options must be accessible to San Gabriel Valley residents to encourage public transit and reduce traffic impacts on the region.

In addition to lack of biking infrastructure, many San Gabriel Valley communities also lack options for outdoor recreation. According to the 2022 LA County Parks Needs Assessment, about 37% of SGV residents live within ½ mile of a park that the County considered to be in “good condition.” However, access to green space including well-maintained parks is not spread throughout SGV communities. The majority of residents in pockets of Alhambra, Monterey Park, Pasadena and San Dimas are more likely to live close to a park considered to be in good condition, while few to no residents in parts of El Monte, Pomona, Baldwin Park, Hacienda Heights and Rowland Heights have access to public green space in the form of a high-quality park. This disparity is again reflected in the variation of tree canopy coverage across the region: 34% of land in Pasadena is covered by tree canopy, compared to just 7% in Irwindale. The differences in park access and tree canopy coverage in the San Gabriel Valley are clear in the maps below.

Learn more about initiatives and advocacy efforts to expand green space access in the SGV below.

The San Gabriel Valley Greenways Network is an initiative that aims to convert storm channels and creeks in the San Gabriel and Rio Hondo Rivers into a network of pathways for people on foot, bike, scooters, and other modes of healthy, affordable mobility. The plan will connect communities and increase access to green spaces for San Gabriel Valley residents, which is particularly important for neighborhoods with low park access and low tree canopy coverage.

In 2014, the San Gabriel Mountains were designated as a National Monument by President Obama to preserve and protect them as natural and sacred lands to help ensure increased access to nature, increase public health, and to help address the climate and biodiversity crisis. Over the following decade, local community based organizations and environmental justice activists advocated for an expansion to the National Monument to enhance access for more than 18 million people who live within a 90-mile radius of the site and the various species living there that are vital to the region’s biodiversity.

Over the last decade, the monument has become infamously overrun with trash and graffiti. In fact, the area was one of nine sites featured on “Fodor’s No List 2024”, a list of international locations that tourists should avoid based on habitat destruction and over-tourism. A lack of oversight and funding were cited as contributors to the amount of litter in the most burdened areas of the monument.

On May 2, 2024, President Biden signed a proclamation expanding the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument by nearly a third, including sections of the Angeles National Forest in the San Gabriel and San Fernando Valleys. Along with the expansion, corporate, philanthropic and state government entities announced over $1 million in support to help ensure equitable access to and sustainable recreation programs in the monument, which is the largest green space in Los Angeles County.

According to the SGV Collaborative, this expanded designation and funding should increase protections of this critical open space for future generations. However, without sustained funding and public awareness campaigns, the habitats and ecosystems within the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument still remain at risk.

Health & Wellbeing

The intersection of high rates of pollution burden and lack of green infrastructure negatively impacts the health of many San Gabriel Valley residents. According to data from the CDC, about a quarter of adults in Los Angeles County don’t regularly participate in any physical activities outside of their job (2020 CDC PLACES). In the San Gabriel Valley, areas with many adults who don’t participate in leisure time physical activity closely align with communities without access to a good quality park. Many of these communities also tend to have higher rates of renters and overcrowded housing, defined as households that have more than one person per one room of their housing unit.

Similarly, many of the same communities experiencing the worst traffic impacts along the freeways in the SGV also have some of the highest rates of asthma diagnosis in the region. Children living close to freeways face an increased risk of developing asthma and experiencing impaired lung function. Research has also found that air pollution exposure is one of the factors that increases the risk of childhood obesity. Similarly, studies are beginning to show links between air pollution and diabetes in certain populations. As of 2019, nearly 50 San Gabriel Valley schools are near a major freeway or road, increasing the risk of asthma and other diseases in communities that are already exposed to trapped smog from the San Gabriel Mountains. Explore the maps below to further understand health trends across San Gabriel Valley communities.

Civic Engagement & Community Power

Given the intersection of environmental and health issues facing the region, the SGV Collaborative is focused on fostering collaboration among environmental, housing, health, and social justice advocates. The initiative prioritizes engaging residents in a culturally and linguistically relevant manner and envisions a future where the highest-need communities are prioritized for investments in:

Greener neighborhoods with cleaner air and water

Affordable, healthy, climate-resilient housing

Equitable digital access

Safer, more sustainable streets for walking, bicycling and public transit

Improved access to parks and open space

Each of the organizations at the table have their own unique history within the community, with a shared ethos of resident empowerment. Read a brief description of each of organization below.

Active SGV

ActiveSGV began as a Facebook Page by community members advocating for safer, people-friendly streets, and currently heads a number of long-term projects and programs aimed at creating a more sustainable San Gabriel Valley.

Avocado Heights Vaquer@s

The Avocado Heights Vaquer@s began as a local group dedicated to preserving the equestrian lifestyle of Avocado Heights and evolved into an environmental justice group centered around community activism

Asian Pacific Islander Forward Movement (APIFM)

Asian Pacific Islander Forward Movement (APIFM)’s Clean Air SGV project was initiated by a partnership with high school youth who were advocating for solutions to the poor air quality at their school, located next to the 10-freeway. This partnership seeded the Sustainable SGV Coalition, a group of residents who guide APIFM’s healthy food access, mobility, air and water quality projects in the West SGV.

Sustainable Claremont

Sustainable Claremont started as an offshoot of the City of Claremont’s Sustainable City Plan back in 2009. The aim was to have a citizens-group to work with the business community and city staff to help implement sustainability efforts.

Healing and Justice Center

Healing and Justice Center began by newly incoming residents of SGV who saw the lack of community organizing, activism and advocacy for tenant rights and affordable housing, compared to more metropolitan areas of Los Angeles County. Their work, rooted in healing and resiliency practices, provides advocates and community the skills to sustain while engaging civically.

Nature for All

Nature for All, beyond our continued advocacy for public land protection and urban parks and green spaces, will soon begin work with the Avocado Heights and other east SGV areas to support community base building efforts. The goal is to ensure that community members are aware of the various environmental impacts they face, learn more about public land protection, restoration, and build their own or join existing community based efforts taking place in the region.

Day One

Day One advances the quality of life in the SGV by convening, connecting and collaborating with communities. Our team hosts weekly Youth Advocate meetings in Pasadena, Pomona, and El Monte. We also convene monthly Partnership for Children, Youth and Family meetings in Pasadena and El Monte. These efforts directly engage communities in solution finding, policy development, and cultivating local leaders.

This ethos of empowering residents as community leaders and advocates is central to the SGV Collaborative. As a collective, table members have been reflecting on how to activate more residents around their community’s health and environmental justice issues. Tactics like meeting residents in shared community spaces such as supermarkets were successful during the isolation of COVID-19. Table members have also been reflecting on ways to meaningfully engage undocumented community members who cannot participate in traditional voting processes, as well as limited English proficient residents who are often excluded from information and participation due to the paucity of in-language materials and access to trained interpreters. Such residents may be able to participate in community collaboratives and oversight committees, such as the San Gabriel Valley Service Council for Metro and the Safe Clean Water Program Regional Oversight Committee. The SGV Collaborative is also pushing local governments to take responsibility for engaging communities in accessible and culturally humble ways. For example, the East San Gabriel Valley Area Plan got community feedback through workshops and community events to get resident input on the update of the area plan.

Through collaborative advocacy, the SGV Collaborative is working towards their vision of creating a more accessible and environmentally conscious community for future generations in the San Gabriel Valley.

Authors & Contributors

Elly Schoen

Elly Schoen (she/they) is the Systems & Data Manager at Neighborhood Data for Social Change, a project of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate. Prior to joining the Lusk Center, Elly worked at the USC Price Center for Social Innovation for six years. Her various roles included building out the Center’s data infrastructure, launching the Homelessness Policy Research Institute (HPRI) and the Neighborhood Data for Social Change (NDSC) platform, and training graduate research assistants in foundational data and research skills. In their current role, Elly continues to manage the NDSC platform, where they work with community-based partners to use data to inform equitable policies and build power in Los Angeles County neighborhoods.

Gabriela Magaña

Gabriela Magaña (she/her) is a Master of Public Policy & Master of Urban Planning dual-degree student at USC’s Price School of Public Policy. Her primary areas of interest are housing policy, homelessness, land use planning, and spatial inequality. Prior to USC, Gabriela graduated with a B.A. in Sociology and a minor in Public Affairs from the University of California, Los Angeles. During her time at UCLA, she was involved in Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (SAJE) and The Tenants Law Firm, where she focused on advancing tenants’ rights and assisting those facing displacement in Los Angeles. Gabriela currently serves as a Student Ambassador for prospective MPP and MUP students, and as a Mentorship Chair for Mentorship for an Accessible Price (MAP).

Other contributors include: Cameron Yap, Emily Phillips and Caroline Ghanbary

Sources

ActiveSGV – Mobility, Climate, Health & Wellness. (n.d.). https://www.activesgv.org/

Cano, M. (2021). 2021 LA County Goods Movement Strategic Plan. Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. https://libraryarchives.metro.net/DB_Attachments/BP-Links/policy-2021-01-20-final-2021-la-county-goods-movement-strategic-plan.pdf

Cheng, W. (2014, August 4). A Brief History (and Geography) of the San Gabriel Valley. PBS SoCal. https://www.pbssocal.org/history-society/a-brief-history-and-geography-of-the-san-gabriel-valley

Fodor’s Editors. (2023, November 7). Fodor’s No List 2024. Fodor’s Travel Guide. https://www.fodors.com/news/news/fodors-no-list-2024

Gomez, M. (2023, August 4). Why conservation of San Gabriel Mountains is crucial for California. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/commentary/2023/08/san-gabriel-mountains-conservation-california/

Greenspon, C. (2024, January 26). ActiveSGV Calls for L.A. County to Fund Eaton Wash Greenway. Streetsblog LA. https://la.streetsblog.org/2024/01/26/activesgv-calls-for-l-a-county-to-fund-eaton-wash-greenway

Han, W. (2011, November 18). Bilingualism and Academic Achievement. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01686.x

How we are engaging with our communities. (n.d.). LA County Planning. https://planning.lacounty.gov/blog/how-we-are-engaging-with-our-communities/

Kleeman, E. (2007, January 26). Living near freeways hurts lungs. San Gabriel Valley Tribune. https://www.sgvtribune.com/2007/01/26/living-near-freeways-hurts-lungs/

Main San Gabriel Basin Watermaster. (2020, February). Overview. San Gabriel Valley Water Company. https://www.sgvwater.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/MainSanGabriel-Basin-Water-Master-Overview-optimized.pdf

San Gabriel Valley Greenway Network. (n.d.). https://www.sgvgreenway.org/

Wigglesworth, A. (2024, May 2). LA Times: San Gabriel Mountains National Monument expands by more than 100,000 acres. Senator Alex Padilla. https://www.padilla.senate.gov/newsroom/news-coverage/la-times-san-gabriel-mountains-national-monument-expands-by-more-than-100000-acres/

Wigglesworth, A. (2024, May 2). San Gabriel Mountains National Monument expands by more than 100,000 acres. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2024-05-02/biden-expands-san-gabriel-mountains-national-monument